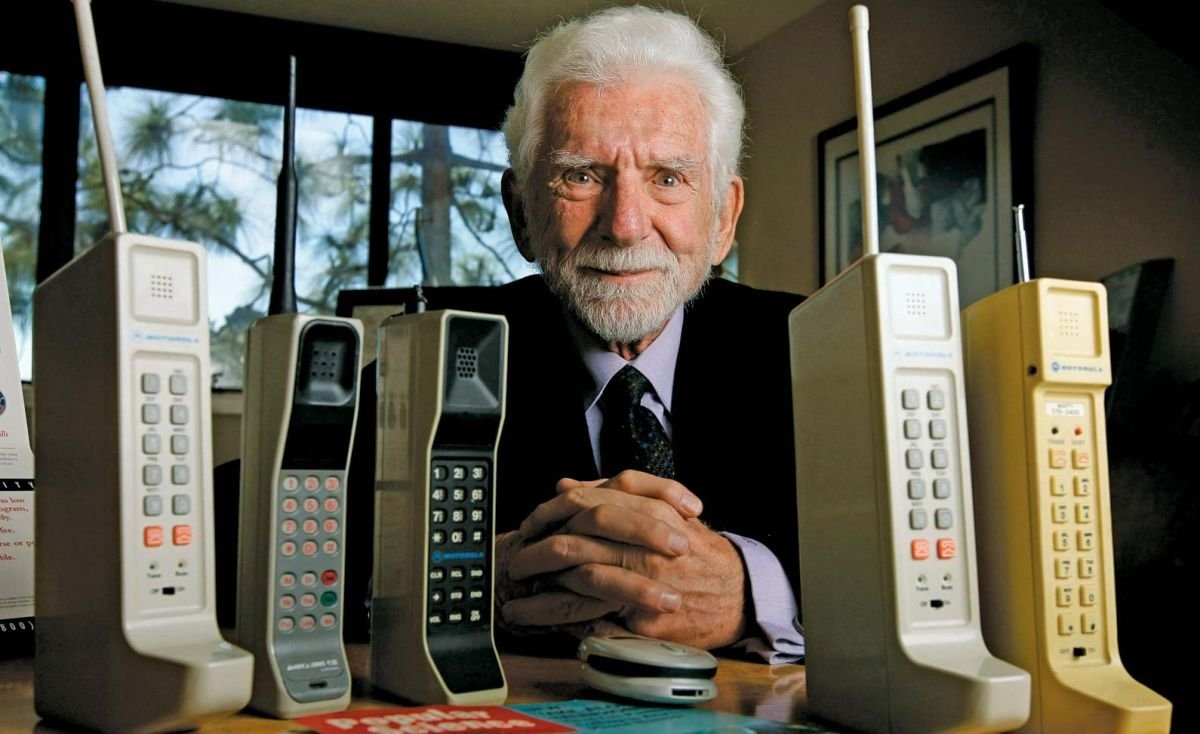

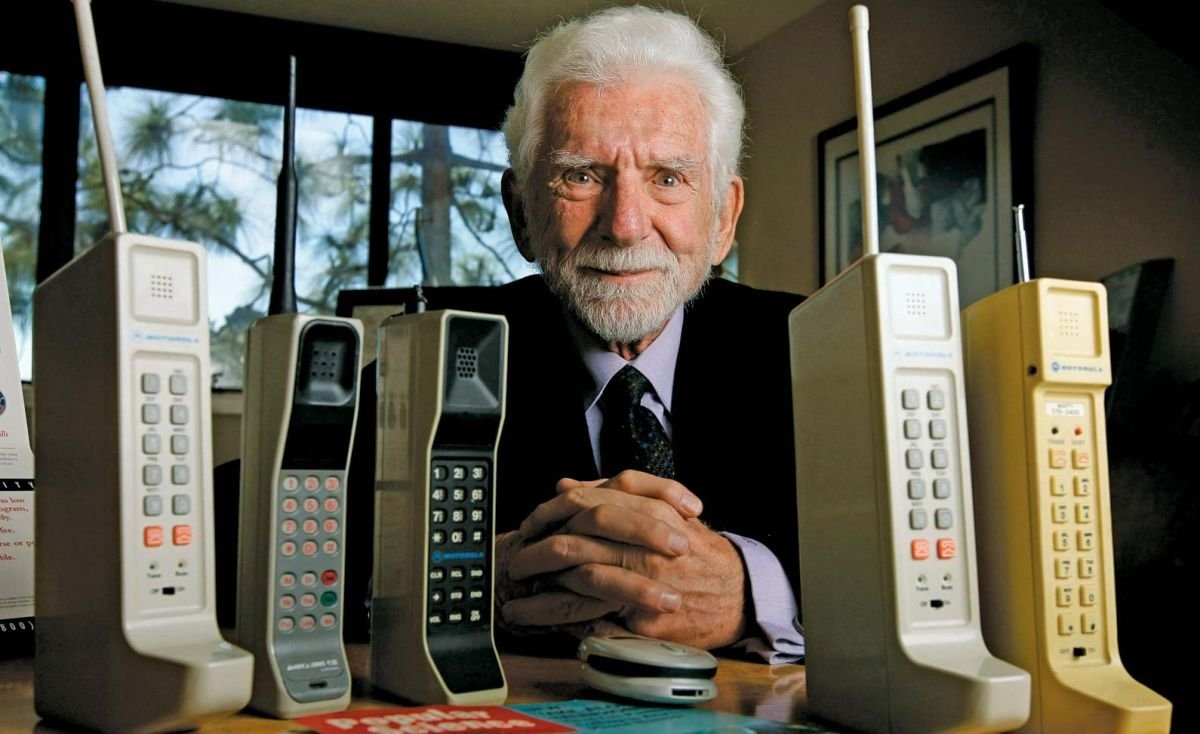

Martin Cooper is an American engineer who invented the first portable cell phone in 1973 while working at Motorola. In addition to being the "father of the cell phone," Cooper is also the first person in history to make a cell phone call in public. The following is an excerpt from Chapter 13 of his new book "Cut the Cord" titled "How the Cell Phone Is Changing Their Lives" which is now available in bookstores and online.

In 2001, approximately 45% of the US population owned a cell phone. Ownership had doubled in the previous four years and quadrupled from the previous six years. On September 11 of the same year, terrorists hijacked planes and launched attacks in New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania. On at least one of the hijacked planes, passengers used cell phones to communicate with family members on the ground. In many places, however, mobile sites had not yet been installed or existing sites lacked the capacity to withstand the surge in mobile phone calls. Many first responders and government officials could not be reached, even over the wired network. On that horrible day, pagers, what many called beeps, were the primary means of disseminating information about the attacks. Although there were three times as many cell phones as pagers, pagers were still widely used to contact and alert people, including at the highest levels of the US government, among White House staff traveling with President George W. Bush, "everyone's pager started going off" as rumors of the attacks spread. There were no phones on Air Force One, which flew the president across the country as they tried to figure out what to do next. The White House press secretary had a two-way pager, not a cell phone, that he could only send and receive a few predetermined responses. The presidential entourage was only able to get updates on the attacks by receiving local television feeds as the plane flew. In the North Tower of the World Trade Center, pagers were the main source of information for those trying to get out. Long lines have formed at public phones in Manhattan. These pagers were the descendants of the first domestic devices that Motorola had introduced thirty years earlier. People want and need to be in touch with each other conveniently, affordably, often immediately, and in an emergency, urgently. Back in the late 1960s, when pagers taught us constant connectivity and cell phones were still a distant dream, I had a science fiction prediction. I told anyone who would listen that one day every person would be given a birth phone number. If someone calls and doesn't answer, it means he's dead. On 11/XNUMX, we had the dark side of that prediction: If you tried to contact someone and couldn't get through, you feared they were dead.

In 2001, approximately 45% of the US population owned a cell phone. Ownership had doubled in the previous four years and quadrupled from the previous six years. On September 11 of the same year, terrorists hijacked planes and launched attacks in New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania. On at least one of the hijacked planes, passengers used cell phones to communicate with family members on the ground. In many places, however, mobile sites had not yet been installed or existing sites lacked the capacity to withstand the surge in mobile phone calls. Many first responders and government officials could not be reached, even over the wired network. On that horrible day, pagers, what many called beeps, were the primary means of disseminating information about the attacks. Although there were three times as many cell phones as pagers, pagers were still widely used to contact and alert people, including at the highest levels of the US government, among White House staff traveling with President George W. Bush, "everyone's pager started going off" as rumors of the attacks spread. There were no phones on Air Force One, which flew the president across the country as they tried to figure out what to do next. The White House press secretary had a two-way pager, not a cell phone, that he could only send and receive a few predetermined responses. The presidential entourage was only able to get updates on the attacks by receiving local television feeds as the plane flew. In the North Tower of the World Trade Center, pagers were the main source of information for those trying to get out. Long lines have formed at public phones in Manhattan. These pagers were the descendants of the first domestic devices that Motorola had introduced thirty years earlier. People want and need to be in touch with each other conveniently, affordably, often immediately, and in an emergency, urgently. Back in the late 1960s, when pagers taught us constant connectivity and cell phones were still a distant dream, I had a science fiction prediction. I told anyone who would listen that one day every person would be given a birth phone number. If someone calls and doesn't answer, it means he's dead. On 11/XNUMX, we had the dark side of that prediction: If you tried to contact someone and couldn't get through, you feared they were dead.

(Image credit: iStockPhoto) I expected, even in the early 1970s, that everyone, everyone, would want and need a cell phone. Others at Motorola shared this expectation of ubiquity because our two-way radio business had shown us firsthand how many businesses performed better when people were connected. Salespeople at Mount Sinai, airport workers, and Chicago police officers have taught us how being connected makes organizations work. We remember the doctors who refused to hand over their pagers so we could repair them. Portable devices like the pager and cell phone, both through mundane use and tragedies like 11/2014, have become anytime, anywhere companions, an integral part of identity itself. These experiences demonstrated a principle of technology that has shaped my perspective for decades. The test of a product's usefulness comes when users become so dependent and attached to it that they don't give up, regardless of failures or negative impacts. The cell phone has proven this time and time again. In a XNUMX Supreme Court ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that mobile phones "have become so ubiquitous and insistent a part of daily life now that the proverbial visitor from Mars might conclude they were an important feature of human anatomy". What even surprised me was the speed and scope of adoption. I never imagined that more people in the world would eventually have access to cell phones than toilets.

Motorola's vice president, John F. Mitchell, shows the DynaTAC portable radiotelephone in New York in 1973 (Image credit: Bettman/Corbis) We tend to overestimate the short-term impact of technology, but underestimate its long-term impact. It's called Amara's Law, according to Roy Amara, a Stanford scientist who led the Institute for the Future think tank for twenty years. Mobile phones are a classic example. In the Motorola DynaTAC fact sheet produced for the media in April 1973, we said that "the cellular telephone is designed to be used 'on the go', when out of the office or away from home. Where conventional phones are not available. "We thought most people were 'on the go' most of the time. And it is even more true now than then.

After cell phones became an operating business, the spark that my team and I ignited didn't ignite much in the Motorola financial community. When we were budgeting for cell phone development, Jim Caile, my marketing manager, showed me a forecast for cell phone sales. We agreed that the first phones would be on the market in the mid to late 1970s. However, the anticipated amounts of product deliveries seemed totally unacceptable to me.

He knew what it would cost for the engineering and other talent needed to develop a manufacturable cell phone. I had done this enough times and underestimated these costs enough times to be confident enough in my estimates. And I also knew that we would never get our leaders to join a plan that sold too few cell phones to recoup that investment. On the other hand, detractors, especially CFOs, would laugh at us if we were as optimistic as we wanted to be.

I looked at the forecast again. "Double all the sales forecasts," I told Caile, "and see if we can sell the plan." He did it conscientiously and the management approved it.

We weren't that far off the sales forecast, but only because most of the early mobile phones were car phones. The laptop was too expensive, and there were not enough mobile sites to support reliable portable communications. In 1990, the performance and size of laptops became more practical, and sales increased rapidly. In 2000, it was hard to buy a car phone; the pocket computer had taken over. In the 2000s, the collapse of landline subscribers began. People didn't believe me when I predicted in the 1970s that the landline phone would be obsolete in the distant future.

However, none of us at Motorola were considering features like cameras in phones. After all, there were no digital cameras in 1973, so it wasn't even on our radar of technological possibilities. Throughout the 1960s, Motorola was a leader in transistors and incorporated them into consumer electronics. This included the DynaTAC, so we had the idea that to improve performance, mobile phones would include more and more transistors. But we certainly did not imagine that the cell phone would become a smartphone, a full-fledged computer. The personal computer was still in development, and the Internet was just developing.

Almost everywhere, predictions about the use and popularity of mobile phones were comically wrong.

In 1984, Fortune magazine predicted that by 1989 there would be one million mobile phone users in the United States. The real figure was 3,5 million. In 1994, consultants estimated that in 2004 there would be between 60 and 90 million mobile phone users in the world. Even the generous margin of error they gave themselves was insufficient: the actual number in 2004 was 182 million.

This is an excerpt from Cutting the Cord, by Martin Cooper, the inventor of the first cell phone.

In 2001, approximately 45% of the US population owned a cell phone. Ownership had doubled in the previous four years and quadrupled from the previous six years. On September 11 of the same year, terrorists hijacked planes and launched attacks in New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania. On at least one of the hijacked planes, passengers used cell phones to communicate with family members on the ground. In many places, however, mobile sites had not yet been installed or existing sites lacked the capacity to withstand the surge in mobile phone calls. Many first responders and government officials could not be reached, even over the wired network. On that horrible day, pagers, what many called beeps, were the primary means of disseminating information about the attacks. Although there were three times as many cell phones as pagers, pagers were still widely used to contact and alert people, including at the highest levels of the US government, among White House staff traveling with President George W. Bush, "everyone's pager started going off" as rumors of the attacks spread. There were no phones on Air Force One, which flew the president across the country as they tried to figure out what to do next. The White House press secretary had a two-way pager, not a cell phone, that he could only send and receive a few predetermined responses. The presidential entourage was only able to get updates on the attacks by receiving local television feeds as the plane flew. In the North Tower of the World Trade Center, pagers were the main source of information for those trying to get out. Long lines have formed at public phones in Manhattan. These pagers were the descendants of the first domestic devices that Motorola had introduced thirty years earlier. People want and need to be in touch with each other conveniently, affordably, often immediately, and in an emergency, urgently. Back in the late 1960s, when pagers taught us constant connectivity and cell phones were still a distant dream, I had a science fiction prediction. I told anyone who would listen that one day every person would be given a birth phone number. If someone calls and doesn't answer, it means he's dead. On 11/XNUMX, we had the dark side of that prediction: If you tried to contact someone and couldn't get through, you feared they were dead.

In 2001, approximately 45% of the US population owned a cell phone. Ownership had doubled in the previous four years and quadrupled from the previous six years. On September 11 of the same year, terrorists hijacked planes and launched attacks in New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania. On at least one of the hijacked planes, passengers used cell phones to communicate with family members on the ground. In many places, however, mobile sites had not yet been installed or existing sites lacked the capacity to withstand the surge in mobile phone calls. Many first responders and government officials could not be reached, even over the wired network. On that horrible day, pagers, what many called beeps, were the primary means of disseminating information about the attacks. Although there were three times as many cell phones as pagers, pagers were still widely used to contact and alert people, including at the highest levels of the US government, among White House staff traveling with President George W. Bush, "everyone's pager started going off" as rumors of the attacks spread. There were no phones on Air Force One, which flew the president across the country as they tried to figure out what to do next. The White House press secretary had a two-way pager, not a cell phone, that he could only send and receive a few predetermined responses. The presidential entourage was only able to get updates on the attacks by receiving local television feeds as the plane flew. In the North Tower of the World Trade Center, pagers were the main source of information for those trying to get out. Long lines have formed at public phones in Manhattan. These pagers were the descendants of the first domestic devices that Motorola had introduced thirty years earlier. People want and need to be in touch with each other conveniently, affordably, often immediately, and in an emergency, urgently. Back in the late 1960s, when pagers taught us constant connectivity and cell phones were still a distant dream, I had a science fiction prediction. I told anyone who would listen that one day every person would be given a birth phone number. If someone calls and doesn't answer, it means he's dead. On 11/XNUMX, we had the dark side of that prediction: If you tried to contact someone and couldn't get through, you feared they were dead.